In a recent article for Responsible Investor for what I’ve called “The state of ESG” series, I argued against a leader article in The Economist that called for ESG to be reduced to a pure “E” focus on climate-related “emissions”.

It’s not because I don’t think there needs to be a laser-like focus on emissions; there does, and urgently.

Indeed, I think it is a good place to start on a “first principles” basis. Let’s use a slightly amended version of the old corporate saw of “what gets measured [properly] gets managed” (my brackets).

This has been an incredibly busy summer of consultation response assessment at the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), the SEC and the EU to some of the biggest changes to corporate reporting regarding sustainability and environmental data, with a large chunk of that on climate (GHG) emissions.

We’ll come back to those initiatives in another article because they are huge in scope and potential impact.

Starting from the bottom up though, I think we need to take a hard look at emissions reporting “as is” to ensure the foundations are fit to support what we are now adding on top, ie heavyweight regulation, net-zero plans, and a host of complex financial products – carbon weighted indices, portfolio-aligned emissions reporting, implied temperature rise (ITR) evaluations or climate-adjusted Value at Risk techniques – not to mention whether climate policy/action is credible.

For some time I have worried that we are building on a bed of sand.

Disclosure deficit

To this end, a FTSE Russell report released this summer titled Mind the Gaps: Clarifying Corporate Carbon caught my eye.

It feels ‘retro’ to be looking at carbon data ‘disclosure’ in 2022, but this is a timely report with a lot of good data assessment in it and some concerning conclusions.

The first is that there are still far too many companies globally that do not report their carbon emissions. The proportion of companies disclosing both Scope 1 and 2 operational emissions (electricity purchased, plus fossil fuels used) in the FTSE All-World Index of 4000+ of the world’s largest companies sits at 58 percent.

The non-reporters include big names such as Berkshire Hathaway and Moderna.

But the real kicker comes when you add in China A-shares: the number of reporters slides to 39 percent.

Only around 23 percent of Chinese companies overall report emissions data, and just 11 percent of China-A share companies.

And despite mandatory carbon reporting requirements on the SEC docket, US firms are still laggards: only 53 percent of the Russell 1000 and 10 percent of Russell 2000 index companies report.

Most worrying perhaps is that FTSE Russell sees little sign of recent improvement. Indeed, it concludes that, just as we need thorough global reporting to shift the world to net-zero CO2, global coverage massively dilutes the credible sum of data.

Does it matter though? Don’t we have viable estimates for Scope 1 and 2 emissions based on sound GHG protocols?

The traditional rule of thumb has been that comparative company estimates are viable with a +/- 10 percent to 15 percent margin of error.

FTSE Russell’s research, however, says that industry or scientific consensus on the best estimation methods falls worryingly short.

It crunched the numbers on all estimated values and found divergence from reported data by 100 percent. This is large enough, it says, to make the weighted average carbon intensity (WACI) of a large, diversified global stock portfolio wrong by several percentage points.

The reality is that most of the problem of Scope 1 and 2 can be solved quite quickly. In essence, much of what is bought and burnt is already in the audited accounts of companies.

Even boundary problems of ownership and control – particularly prevalent in the oil and gas industry – can be ironed out.

However, regulators must regulate, and companies and investors should help by pushing strongly for a level playing field on reporting. This should be an engagement priority.

FTSE Russell is calling for mandatory disclosure. Jaakko Kooroshy, global head of sustainable investment research at the firm, told Responsible Investor: “There is little prospect of closing these gaps through voluntary measures. It’s amazing really what we have achieved through effectively pushing large companies to disclose such a material data point voluntarily.”

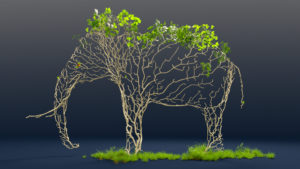

The emissions elephant

Of course, all of this comes before we start discussing the elephant in the room: Scope 3 emissions (supply chain and product use, or upstream and downstream).

Estimates put these at circa 70 percent of emissions for some companies. For example, oil and gas companies tend to be good Scope 1 and 2 reporters, but their Scope 3 emissions for use of products are where the story is.

Paul Dickinson, founder chair of CDP, which collects the emissions data for 13,000 companies companies globally, says he is relatively relaxed about progress on Scope 1 and 2 reporting. CDP accounts for approximately 65 percent of largest global market cap companies on Scope 1 and 2.

On Scope 3, he says it is still the “Wild West”, albeit with potential for serious change if the number of reporters can be optimised. “If the upstream supply chain is reporting Scope 1 and 2 emissions and attributing them to you as a customer, then we’re kind of there.”

The complications, he says, come from “the biological end of things” – the drivers of deforestation or the wholesales purchasers of “anything that grows” and the downstream users of vehicles, for example.

On the latter, he thinks that electronic data from vehicle companies could go some way to solving the problem.

However, he says one of the most complicated entities in terms of climate change are supermarkets, because the supply chain and the product use are incredibly complex.

“My favourite example within this complexity is the cow that produces milk and meat over its life cycle. How do you divide the emissions between the two?

Kooroshy at FTSE Russell believes that in certain sectors where Scope 3 emissions clearly need to be attributed – autos, oil and gas, financials – then reasonable proxies need to be clarified and deployed quickly. “We can look at oil production, for example, and all the parties using oil, and then multiply that by the emissions created from combusting a barrel of oil.”

CDP’s Dickinson warns, however, that getting the data right is not, of course, a proxy for action, nor is piling up data collection systems.

“For over two decades now at CDP we have installed carbon x-ray machines for companies. X-ray machines are a vital part of the medical process. But no one has ever been cured by an x-ray machine. And if you have a hospital full of x-ray machines, the patients will not get better. If, in the UK for example, you introduce a £100 per tonne ($114; €114) CO2 tax, which is probably necessary for human survival, then I can promise you that every single tonne of CO2 in the UK will be fully audited immediately.”

Driving change

Dickinson is optimistic that two major corporate/investor initiatives will drive real change on the policy/pricing issue.

The first is the Science-based Targets initiative (SBTi), which is working with 3,000 companies to the carbon budgets developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and International Energy Agency (IEA), in tandem with scientists.

The second is the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), which represents more than $130 trillion in assets under management and advice.

Dickinson says: “These are both basically net zero by 2050 drives. This is where it gets interesting. Either the science-based targets of all the corporations are greenwash or governments are going to have to pass laws to achieve them.

“As we see more and more extreme weather conditions and serious energy pricing conundrums occurring, all eyes are now on governments to respond. I can see NGOs, investors and corporations moving fast now in partnership with governments to get the laws to enable the 7 percent per year CO2 reductions we need.”

We certainly need to get the data-policy-pricing horse and cart aligned.

Mandatory emissions reporting requirements for listed corporations in the UK have worked well, and are now being proposed by the SEC in the US, and by Japanese regulators.

This needs to be turned into a unified, global push, with clear meaningful calculation efforts across Scopes 1-3, and into unlisted companies and state-owned entities.

Then pragmatic, gradual policy and price tightening – an even bigger challenge, of course – can at least be built on solid foundations.